- English

- Français

- Nederlands

The Obscure Cities: An Introduction

by Julian Darius, published before at Sequart Research & Literacy Organization on Monday, 11 July 2011

The Obscure Cities (Les Cités Obscures) arose in the midst of a pivotal time in the history of French comics.

So let’s talk about French comics, shall we?

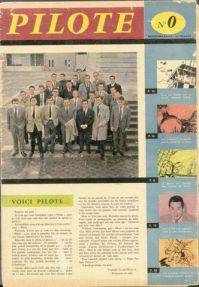

In the early 1970s, French comics were dominated by the influence of the anthology magazine Pilote. Pilote had always been a kid-friendly affair, going back to its founding in 1959. The two creators of the beloved character Astérix had been among the magazine’s co-founders, and Astérix himself debuted in Pilote. By the 1970s, however, Pilote was struggling to accommodate its creators’ desires to produce more sophisticated material.

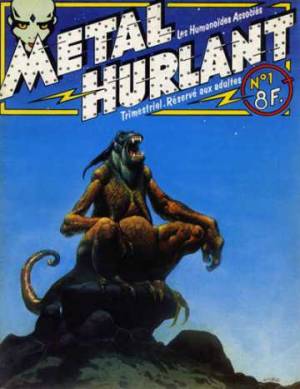

Jean Giraud was among these creators, having produced for Pilote the Western Blueberry from 1963-1973. He came to believe that Pilote wasn’t the right vehicle for adult comics, so he left and, in 1974, co-founded a rival anthology, Métal Hurlant (Screaming Metal, though its sister U.S. publication is Heavy Metal). Using the penname Moebius, Giraud began producing groundbreaking work for the title, such as Arzach, a short-lived (and now iconic) fantasy series begun in 1975 starring a warrior who rode a pterodactyl-like creature. The series had the distinction of being entirely silent, a great innovation for the time. In 1975-1976, Moebius worked on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s abortive Dune film, and the two rolled some of their ideas for the film into The Incal (l’Incal), a wild six-volume sci-fi series published from 1981-1989.

Jean Giraud was among these creators, having produced for Pilote the Western Blueberry from 1963-1973. He came to believe that Pilote wasn’t the right vehicle for adult comics, so he left and, in 1974, co-founded a rival anthology, Métal Hurlant (Screaming Metal, though its sister U.S. publication is Heavy Metal). Using the penname Moebius, Giraud began producing groundbreaking work for the title, such as Arzach, a short-lived (and now iconic) fantasy series begun in 1975 starring a warrior who rode a pterodactyl-like creature. The series had the distinction of being entirely silent, a great innovation for the time. In 1975-1976, Moebius worked on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s abortive Dune film, and the two rolled some of their ideas for the film into The Incal (l’Incal), a wild six-volume sci-fi series published from 1981-1989.

American and British comics were busy maturing during this time too. In the mid-1970s, Métal Hurlant seemed miles beyond comics in English, which were largely busy trying to make super-hero stories more topical and just slightly less ridiculous. By 1981, the year the first volume of Incal was published, English-language comics were catching up with Frank Miller’s work on Daredevil. The following year, as the second volume of Incal was published, Alan Moore began his seminal work on in the U.K. anthology Warrior. 1986 saw Dark Knight Returns. The masterpieces that marked a watershed moment in American comics history, The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, were published in 1986-1987, between the fourth and fifth volume of Incal, by which point English-language comics may be said to have caught up, if not surpassed, their French counterparts.

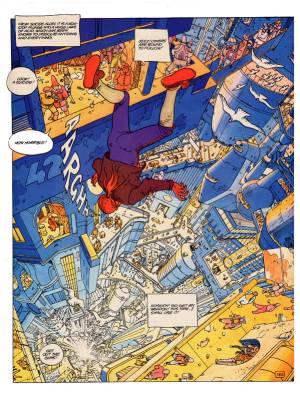

It’s not too much to say that The Incal (though begun earlier, a sign of how advanced French comics were at the time, it was completed later, owing to the slowness of French artistic production) was the French equivalent of The Dark Knight Returns or Watchmen. These works represented the full flowering of earlier trends toward more mature comics narratives; though by different publishers, Warrior led to Watchmen in the same way that Métal Hurlant led to Incal. They were works that everyone in their respective nations read and which would go on to exert a profound influence. All were extended narratives (Incal runs about 300 pages, halfway between Dark Knight and Watchmen). All were also dystopian genre works. But while the U.S. works were predictably within the super-hero genre, Incal is in the sci-fi / fantasy genre in which Métal Hurlant specialized.

Those who disparage the dominance of U.S. comics by the tropes of the super-hero genre will find Incal hardly any improvement. It’s a sort of mystical space fantasy filtered through the tarot, and it’s filled with obvious names, tongue-in-cheek jargon, and little character development. And like its inspiration Dune, Incal is a sci-fi world that has characters with super-powers. In other words, while it a crucial touchstone, it’s still very much a genre work. It’s also a rather uncontrolled narrative, gathering characters and outrageous concepts rather than resolving them in any sort of ordered fashion. In other words, it’s a far cry from Watchmen, which mitigates its genre through its careful control, literary values, and realism.

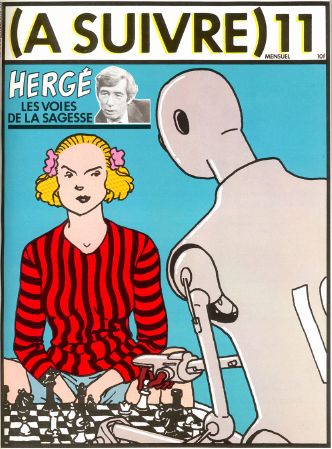

But while Métal Hurlant and Incal were pushing French sci-fi and fantasy comics into more adult territory, Belgian publisher Casterman had been doing the same with less outlandish generic tropes. In 1973, the same year Jean Giraud completed his work for Pilote, Casterman brought out Hugo Pratt’s celebrated war comic Corto Maltese. Frank Miller, an admirer of Pratt’s work, borrowed the name Corto Maltese for an island in Dark Knight Returns (which led to it later being mentioned in other DC Comics and Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman). In 1978, four years after Moebius co-founded Métal Hurlant, Casterman brought out its own adult-focused anthology, titled (À Suivre) (which literally translates as “to follow” but which is used at the end of stories in the same way we use “to be continued”). À Suivre published genre work too, although it tended to be a bit more intellectual and less bombastic than Métal Hurlant.

But while Métal Hurlant and Incal were pushing French sci-fi and fantasy comics into more adult territory, Belgian publisher Casterman had been doing the same with less outlandish generic tropes. In 1973, the same year Jean Giraud completed his work for Pilote, Casterman brought out Hugo Pratt’s celebrated war comic Corto Maltese. Frank Miller, an admirer of Pratt’s work, borrowed the name Corto Maltese for an island in Dark Knight Returns (which led to it later being mentioned in other DC Comics and Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman). In 1978, four years after Moebius co-founded Métal Hurlant, Casterman brought out its own adult-focused anthology, titled (À Suivre) (which literally translates as “to follow” but which is used at the end of stories in the same way we use “to be continued”). À Suivre published genre work too, although it tended to be a bit more intellectual and less bombastic than Métal Hurlant.

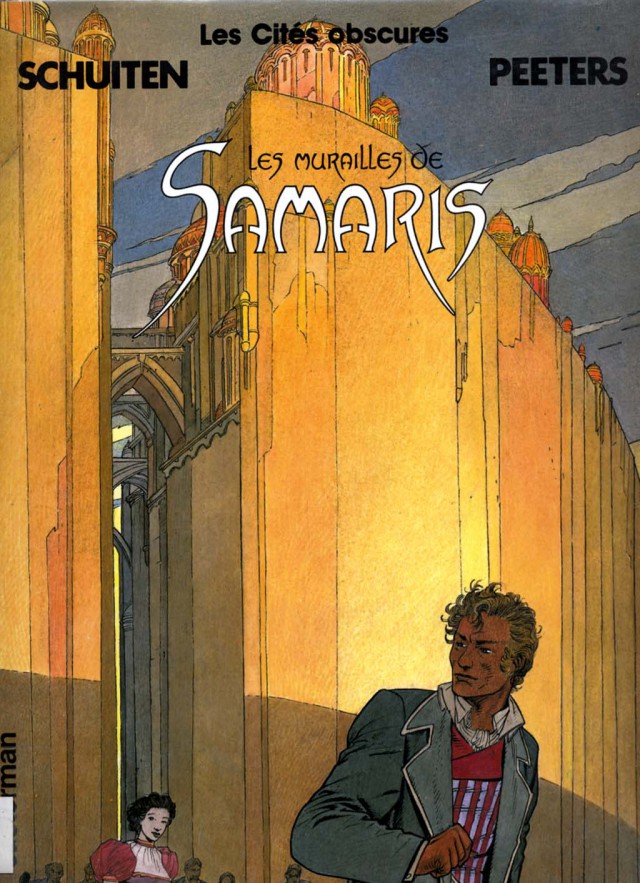

It was in the pages of À Suivre that artist François Schuiten and writer Benoît Peeters began The Obscure Cities. Schuiten, born in Bussels, had created a single short story for Pilote, published in 1973, and then worked for Métal Hurlant in 1977. With Peeters, his friend, he came up with the idea for the first Obscure Cities book, The Walls of Samaris (Les Murailles de Samaris), then not planned as part of a series. Its first installment ran in June 1982, the same year Moore began his work in Warrior and the second volume of Incal was published. Collected in 1983, it was chosen as one of the 20 best books of the year by the French literary magazine Lire (To Write).

Schuiten’s parents were both architects, and his love of architecture came out in Samaris. Set in two fictional cities, Samaris gave Schuiten the occasion to design entire cities using exaggerated homages of past styles, especially Art Nouveau. For this, Schuiten drew particular inspiration from Victor Horta, the Belgian Art Nouveau architect responsible for much of 19th-century Bussels.

With Samaris, Schuiten and Peeters had developed the brilliant idea of merging (1) Schuiten’s stunning capacity for rendering fantastic architecture with (2) philosophical plots. From this point on, all of Schuiten’s work would have this focus, to one extent or another, to such a degree that he would later design metro stations in Brussels and Paris, a mural in Brussels, and pavilions for world’s fairs

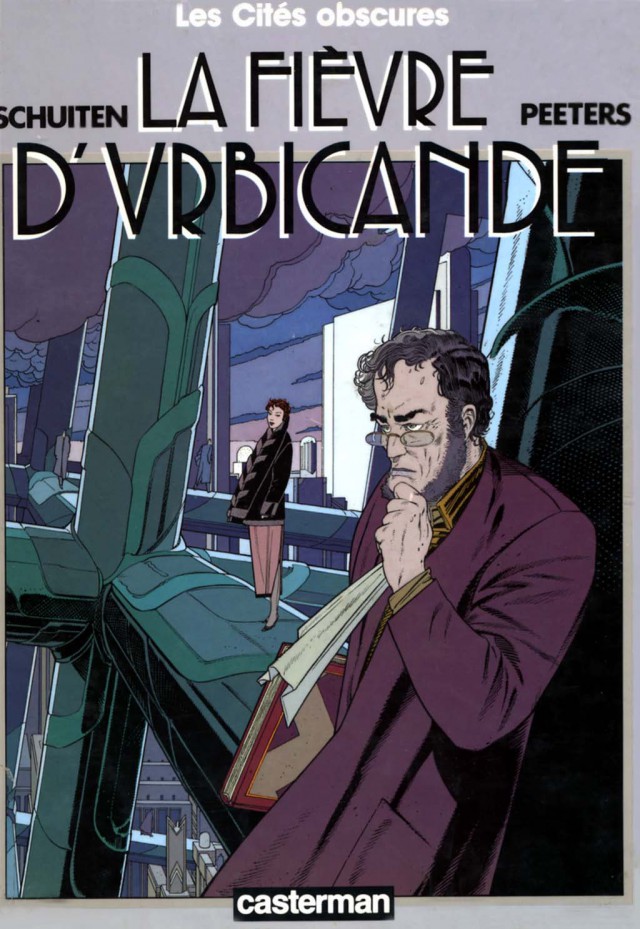

Schuiten and Peeters soon developed a successor volume, The Fever of Urbicande (la Fièvre d’Urbicande), that would make architecture and its implications more directly the story’s focus than in The Walls of Smaris. Serialized in À Suivre, The Fever of Urbicande was collected in 1985, the year the fourth volume of Incal and the year before The Dark Knight Returns and the beginning of Watchmen. Urbicande’s philosophical story won even more acclaim and influence than its predecessor. It won the coveted Prize for Best Album (Prix du Meilleur Album), also known as the Golden Wildcat (Fauve d’Or), at France’s Angoulême International Comics Festival.

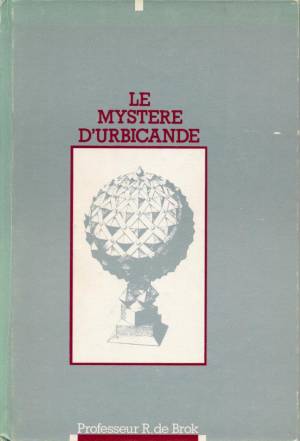

The same year the collected The Fever of Urbicande was published (1985) saw a short sequel, “The Mystery of Urbicande” (Le Mystère d’Urbicande). Surprisingly, it wasn’t published by Casterman but by Schlirf Books, and it was limited to 1900 copies. It consisted of about 25 pages of illustrated text, in a smaller format, like that of an academic press book. In fact, it purported to be just that: an academic dissertation by one Professor R. de Brok, annotated in the margins by Eugene Robick, the protagonist of The Fever of Urbicande. Essentially, it appeared to be an object from the world of The Obscure Cities, and it marked a turning point in the series.

Suddenly, The Obscure Cities wasn’t simply a series of French graphic novels. It seemed to take on a life of its own, including works in multiple formats, some of which were in-world artifacts and not all of which were comics. The scarcity of the aptly-named “Mystery of Urbicande” only made its legend increase, and rumors circulated about its production and its content. As the series continued, its experiments with format would become one of its defining characteristics, setting it apart from any other series.

Although produced in the same period, The Obscure Cities stands in stark contrast to other attempts at mature comics. The series is best classified as science fiction, and each volume generally features at least one element of the fantastic. But Obscure Cities has less in common with Incal, also ostensibly philosophical sci-fi, than Incal with Action Comics.

For all of its fantastical elements, not the least of which is its urban landscapes, The Obscure Cities is as stunningly realistic as Schuiten’s depictions. Watchmen, at its most sophisticated, isn’t about super-heroes at all but about their impact upon society and the human psyche. The Obscure Cities similarly doesn’t focus on its fantastical elements as much as on their implications, in a way that radically outstrips Watchmen. The stories of The Obscure Cities are about people, and nowhere are there the melodramatic stakes of Incal, Dark Knight, or Watchmen. There’s hardly a physical conflict in the entire series. Many stories end without any sense of overcoming the social and psychological conflict that is present. Yet the stories themselves, while definitely cerebral, are nothing short of enthralling.

The Obscure Cities also has real philosophical depth. Sure, Incal plays with the tarot and with Manichaean dichotomies of good and evil (much as Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing later would). Sure, Dark Knight Returns plays with Ayn Rand. Sure, Watchmen plays with Nietzsche. But The Fever of Urbicande explores how architecture subtly changes society (an idea Alan Moore later took up, less successfully, in his incomplete Big Numbers and, diluted by mixing with magic, in From Hell). A later volume, Brüsel, explores how progress can undermine a culture’s sense of history or patrimony, using architecture as its metaphor. Another later volume, The Invisible Frontier, explores the political and psychological implications of cartography. The difference between this and most smart comics is like the difference between reading Nietzsche and reading a crib sheet for Nietzsche.

Not that there’s anything wrong with simply playing with deeper concepts in service of a plot, and several volumes of The Obscure Cities do this too – but they’re resonant, often haunting plots, not ones driven by action. For example, the very first volume, while lacking the philosophical depth of The Fever of Urbicande, plays subtly with notions of reality and fiction, including the comics form itself.

While we’re on the subject of the comics form, the series also began experimenting with format with The Fever of Urbicande. French hardcover album collections almost universally ran 48 pages, give or take, but The Fever of Urbicande ran almost twice that. In this way, the series was breaking its nation’s limits of existing formatting conventions much as Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen later would. In this respect, it’s worth pointing out that the French were already far ahead of the game: their albums, as oversized (relative to a U.S. comic) hardcovers printed on good paper, were already beyond where these U.S. comics that broke the mold dared to go. Some, like Astérix le Gaulois, remained in print for decades, analogous to the trade paperbacks U.S. publishers had only barely started experimenting with. As The Obscure Cities continued, additional longer volumes would contribute to a general relaxation of restrictions on French album length.

Also with The Fever of Urbicande, the series began experimenting with narrative text pieces, not unlike Watchmen’s back matter, although incorporated into the narrative itself rather than being relegated to a back-up. The Mystery of Urbicande also uses this format. The next volume of The Obscure Cities, 1987’s The Archivist (l’Archiviste), wouldn’t even tell a standard comic-book story at all, instead using illustrated text and, in the original printing, tabloid-sized pages. This experimentation with format would eventually come to include a children’s book, an audio play, and a movie, as well as several documents pretending to be from the world of The Obscure Cities but produced, unlike Watchmen’s back matter, as their own independent objects, with dimensions adjusted as appropriate.

In other words, while French comics were busy with their first “mature” magnum opus (Incal) and English-language comics had only taken tentative steps towards their own, The Obscure Cities had already begun to do far more mature and sophisticated material. Like those other examples, this material was still within a genre identified with pulpy fight scenes and damsels in distress. But at a time when comics were struggling from adolescence into young adulthood, The Obscure Cities suddenly presented a fully-fledged adult vision – not only an adult vision, but a truly intellectual one.

It was out-sophisticating the sophisticates.

And it still does.

It particularly deserves a special attention for English-speaking audiences. French food, clothing, literature, cinema, and even comics have long held a certain cultural cache in the U.S. This cache ebbs and flows. It is, in some cases, based on truth. Generally, when the French have an equivalent of a food item eaten by Americans, the French version is in some way superior; they take gastronomy very seriously. Similarly, it’s easy for Americans with even the most superficial understanding of French comics to marvel at the high production values of French hardcover comics albums. And yes, they’re products of a system that requires only one such album per year (or two) for an artist to be deemed suitably productive. And yes, they can sell in the millions, particularly if they’re Astérix and despite their tremendously high price compared to U.S. comics. And yes, they’re relatively self-contained, free of corporate continuity. And yes, they’re in large, well-ordered sections of bookstores, not relegated to specialty shops. And yes, you do see normal-looking people reading them in cafés.

On the other hand, the French mystique often doesn’t survive a closer examination, at least in unscathed form. Sure, the French make some great and offbeat films, but they also dub foreign films into French, which in American culture is a lowbrow move because it alters the original much more radically than subtitles. Similarly, once you start seriously perusing those French comics albums, you find that, while they’re almost entirely free of super-heroes, they’re filled with silly and stupid examples of all sorts of other genres. Action heroes in French comics don’t speak in existential parables; their dialogue is just as bad as it is in U.S. fiction. Just because art has high production values and doesn’t have to be shrink-wrapped or carry a warning label to show full-frontal nudity doesn’t by itself mean that the average person making that art is significantly more intelligent or capable. Incal has its drawbacks, but it’s still popular in France – and it deserves to be, because it’s wildly above average there as it is here.

But The Obscure Cities? It’s pretty much what Americans want French comics to be. Intoxicatingly beautiful. Elegant, even. Willing to experiment. And smart in a way that it’s easy to lose yourself in the rich resonance.

A Note on Translation

It’s even more of a shame, then, that the series hasn’t been fully published in English. In addition, most of these editions are out of print.

Odds are therefore good that the reader of this book, unless he or she also reads French, hasn’t read the complete series.

To make matters worse, fans of the series have often complained about the quality of the translations, particularly about occasional liberties taken in translation. (These extend to the title of the series itself, given in English as Cities of the Fantastic, though more on that in a moment.)

To my mind, a bigger problem with the translations is that they, while largely “correct” to the original meaning, often lose the original’s tone completely. With The Obscure Cities, tone is especially crucial, because that tone is often philosophical. Many characters ponder their situation, and their language can often be a bit formal. This tends to slow the reader down, letting the mind appreciate the story’s evocations while the eyes peruse the detail of Schuiten’s illustrations. In this way, the richness of the words and that of the pictures can sometimes work together marvelously. Too often, translations of the series have rendered interesting syntactic formulations in the most mundane way possible. This might appeal to the American penchant for informality and directness, but it greatly reduces the philosophical feeling many stories engender in their original. This combines with the fact that Americans (relative to the French) are habituated to read comics quickly (arguably because they’re cheaper but also because of the way American comics are paced). The result can too often be that readers race through a volume of The Obscure Cities without pausing to think – or worse, to create a disjuncture between mundane words and beautiful pictures that is often not present in the original French.

Some alternative translations are available online, and these may be consulted while reading the French originals.

Cities of the Fantastic?

Translation problems even extend to the series title. In English, “obscure” means that a work is difficult to understand, while “obscured” means that an object cannot be (fully) seen. But in French, “obscure” retains its Latin meaning of “dark” (or “darkened,” an effect of having been “obscured”), and this carries the possibility of menace.

The title shouldn’t be taken to imply that the series is “obscure” or difficult, and there’s nothing particularly “dark” about the series either. Rather, these meanings apply to the series’s fictional cities. Each city may well be hard to understand for outsiders, an idea rooted in the first volume, where the possibility of menace is most felt. It’s initially a conceit of this world that most cities don’t know much about one other, rendering them obscure. Similarly, the overall world of the series is vast and can be hard to understand. Much of the world hasn’t been shown or has only been shown at a certain historical point, rendering much of it still obscure. It also becomes clear, later in the series, that this world is a counter-Earth, rotating opposite Earth in the same orbit, and in this sense, the entire world is “obscured” from Earth’s view.

In the existing published translations, the series is titled Cities of the Fantastic (and in one case, the more ridiculous Stories of the Fantastic). While this takes a certain degree of liberty, it’s not hard to see why it was chosen and kept. Foreign works (especially intellectual French ones) have enough of a reputation for being “obscure,” and the word “obscured” only underlines the difficulty of translation. “Dark” would be inappropriate, given that there’s nothing particularly “dark” about the series, especially compared to violent and dystopian American comics. (Dark Cities, while a perfectly acceptable title, also must contend with the 1998 film Dark City.) Rather than suggesting anything dark or obscure, Cities of the Fantastic instead suggests the obverse: a sense of wonder. And that’s not altogether inappropriate to the series, although the characters themselves generally aren’t filled with wonder at their settings. Furthermore, this choice of title has a ring to it of pulp adventure that doesn’t fit the material.

Many fans prefer the more literal translation of the title, The Obscure Cities, and this has been retained here.