- English

- Français

- Nederlands

The Fever of Urbicande, Chapter 1

by Julian Darius, published before on Sequart Research & Literacy Organization at Monday 7 November 2011

We’ve previously looked at The Fever of Urbicande‘s prologue and some of its implications. This time, we’ll dive into the story itself.

Also, I’ve previously introduced The Obscure Cities series and discussed its first volume, The Walls of Samaris. You don’t need to read them to understand The Fever of Urbicande, but they’re there if you’d like more.

Chapter 1

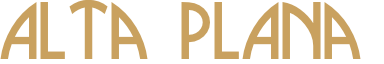

The Fever of Urbicande is narrated by Eugen Robick’s journal entries, complete with dates (lacking years). The caption in the story’s first panel thus begins “24 June.” After this, Robick notes solely “Impossible to work this morning…”

It’s a brilliant first line. And like the first line of The Walls of Samaris, it encapsulates a good deal of the feeling of the story.

The line suggests impotence. Robick, who identifies so proudly as an urbatect that he puts it larger than his own name on his stationary, clearly takes pride in his work. Yet he finds himself unable to. And his reason is that he’s fascinated by an enigma.

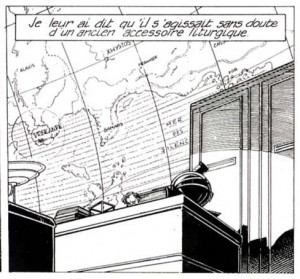

It’s a simple enigma. A hollow, apparently indestructible cube, defined solely by its outline. Robick narrates that it was brought to him by Klaus and Friedrich, whom Robick apparently knows, after it was “exhumed” at one of Urbicande’s many construction sites. Robick admits there’s “nothing too remarkable” about it: “It’s a simple cubic structure, totally empty.” Yet he finds it “curious,” most of all because it serves no apparent purpose. He suggests it must have been an ancient liturgical accessory — though he narrates that this is what he told Klaus and Friedrich, suggesting he may be less certain.

That’s all that happens on the first page: we zoom out from this cube, and Robick looks thoughtful as he examines it and takes notes.

Of course, his statement that it was “impossible to work this morning” undermines his simple explanation. He’s fascinated, almost despite himself, with this odd object too. He may define himself as an urbatect, but there’s clearly a larger intellectual curiosity at play within him.

We readers will soon come to share his fascination, and the story will play upon (and depend upon) our own capacity for intellectual curiosity. Because despite the prologue, which establishes Robick’s conflict with the High Commission as the story opens, the story won’t ostensibly concern itself with those concerns at all. Believe it or not, the story will be entirely about this cube and its implications. This is its story, even more than it is Robick’s.

And already in the first panel, we see that cube, in detail, suggesting its place within the narrative. In close-up, it’s so large that it’s cropped by the panel borders. And though it’s merely sitting on Robick’s desk, it’s denting the papers on which it’s been set, imposing itself on its environment just as Robick’s construction projects have imposed themselves upon historic Urbicande. It’s a subtle visual hint but a masterful one.

As the story continues, Robick gives another explanation for his fascination: Klaus and Friedrich wanted him to come to the construction site, to see where the cube was unearthed, and he had to spend “over an hour” convincing them it “would serve no point.” But already, the narrative is busy undermining Robick’s claims of certainty and dispassion. Because he soon picks up the cube again, as if his curiosity has not abated. And Thomas, apparently his friend, quickly arrives for an appointment that Robick narrates he’d utterly forgotten about.

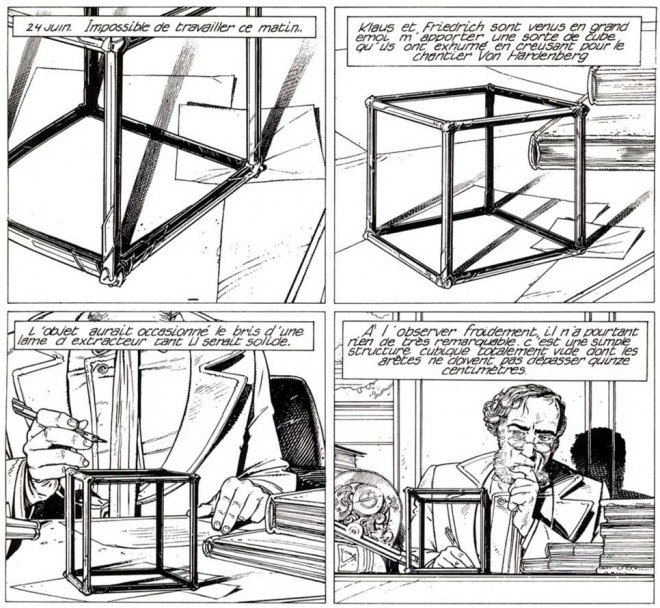

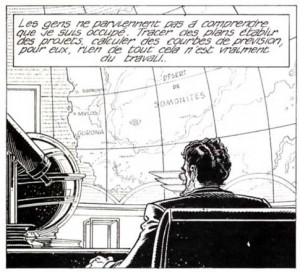

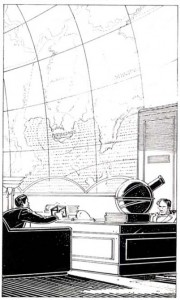

As the proverbial camera rotates around Robick’s office, we see an enormous, curved map on his wall, which gives us the first look at the geography of this world. In the first panel is Xhystos and Samaris, looking very much like the portion of map seen in The Walls of Samaris. In the same panel, we also see Urbanicande’s location, to the west of the previous volume’s terrain, with the city of Alaxis to Urbanicande’s north. As we continue to rotate, we pass Green Lake and see a vast continent, terminating against an ocean with the cities Sodrovni and Mylos near the coast. We will see all of these cities as the series continues, as if Schuiten and Peeters would flesh out this map with stories, making these dots live. If two volumes make a series, it’s in this sequence, on pages one and two of that second volume, that the isolated area covered by The Walls of Samaris gets a world for the first time.

As a further indication of Robick’s fascination with the cube, the appointment with Thomas isn’t a trivial one. It’s about Bridge Three, which was the apparent principle conflict in the prologue. The High Commission has decided to advise against Robick, meaning the plan with “very probably” be refused.

Thomas puts into words what was only implicit in Robick’s letter: that the High Commission “believe[s] that passage between the North Bank and the South Bank will become too easy.” Implicitly, the government wishes to restrict movement, to keep the poorer half of the city separated from the wealthier half. It needs to be pointed out that this isn’t some fictional conspiracy theory: it’s a very real-world consideration which has been applied to U.S. cities — just think of all the objections, every time public transportation lines have been extended to poorer, especially minority areas.

At this point, Robick has become concerned. He doesn’t take the loss of Bridge Three lightly. But Thomas isn’t apparently so passionate, and he begins to fiddle with the cube sitting on Robick’s desk. It’s as if there’s something hypnotic about it, something curious about it that compels the attention.

At this point, Robick has become concerned. He doesn’t take the loss of Bridge Three lightly. But Thomas isn’t apparently so passionate, and he begins to fiddle with the cube sitting on Robick’s desk. It’s as if there’s something hypnotic about it, something curious about it that compels the attention.

Robick explodes irritably at Thomas. But Thomas remains calm and suggests they go to speak to the High Commission in person.

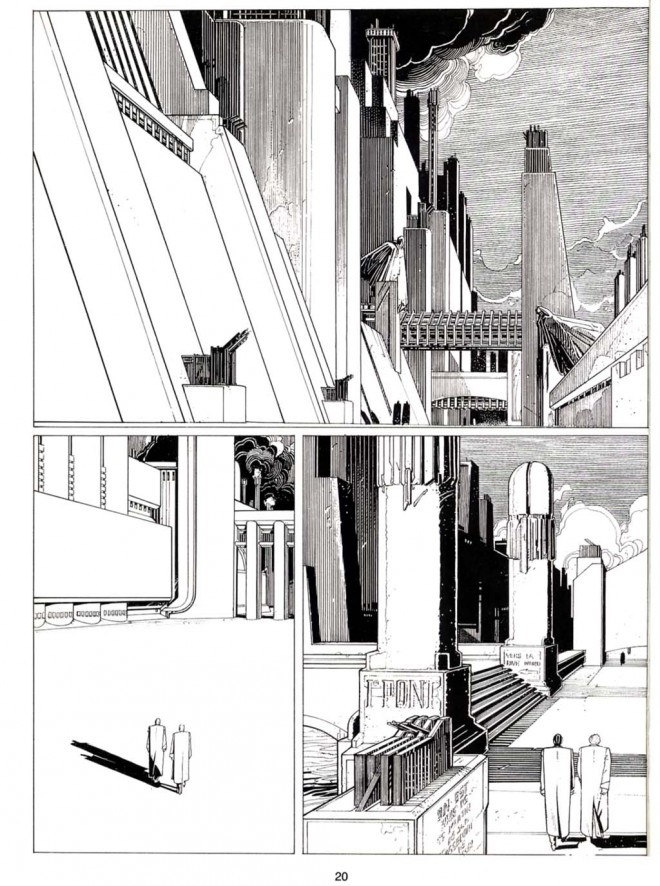

The following page provides the first view of Urbanicande, and it’s one of towering skyscrapers. A key focus is the river that divides the North Bank from the South. Eugen and Thomas happen to pass Bridge One, which is labelled so that we know they’re on the South Bank. The two banks also appear to be very different: while both are filled with skyscrapers, the poorer North is churning out thick, black, industrial smoke. And the South has a pleasant, wide, open walkway along the riverbank (although one lacking in vegetation), while the North has none. Those skyscrapers look very much like walls, blocking one side from the other. Even more ominously, Bridge One a notice that travelers over it are obliged to present their passports, another indication that the state is concerned with controlling movement between the two sides. Schuiten’s art is undeniably beautiful, and yet there are clear hints of a dark aspect to this utopia.

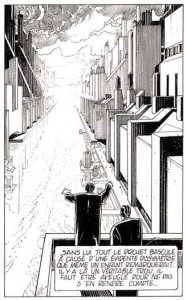

From a vantage point that allows us to overlook the river, Eugen Robick explains why Bridge Three is so important to him: he’s constructed the whole assuming the presence of a bridge that is now being denied him. Fists raised high, he rails against the “obvious dissymmetry that even a child would notice.” It is, for him, a “hole” in the city, a lack that “you’d have to be blind not to see.” Thomas assures Eugen he’s already convinced, and Eugen apologizes for his enthusiasm.

From a vantage point that allows us to overlook the river, Eugen Robick explains why Bridge Three is so important to him: he’s constructed the whole assuming the presence of a bridge that is now being denied him. Fists raised high, he rails against the “obvious dissymmetry that even a child would notice.” It is, for him, a “hole” in the city, a lack that “you’d have to be blind not to see.” Thomas assures Eugen he’s already convinced, and Eugen apologizes for his enthusiasm.

The pair enter the High Commission’s massive building, then an equally massive waiting room, where they bureaucratically request to speak. It recalls the end of The Walls of Samaris, in which Franz requests an audience with the council of Xhystos — except that there, displaced in time, he was mocked, whereas Eugen and Thomas seem more respected and more powerful in their city’s bureaucracy.

While they’re waiting to hear if they’ll be allowed to enter, Thomas takes the opportunity to ask about the cube on Robick’s desk. Despite volunteering the idea of speaking to the commission, he’s calm about Bridge Three. Yet he’s still curious about the cube, which he clearly can’t get out of his mind. In contrast, Eugen responds, “A cube? What cube?” Despite his earlier fascination with the cube, he’s now forgotten it utterly, lost as he is in trying desperately to save his original design for the city.

The commission does agree to see Robick. Inside, it’s anything but the faceless bureaucrats that Franz encounters, perched pompously high. Instead, the commission consists of five men seated comfortably in chairs around an elegant table, suggesting how comfortable they are with their privilege. The commission member at the head of the table — the only one who speaks — is overweight, subtly suggesting that he’s used to life high on the hog. It certainly indicates a certain amount of corruption, but it’s more a sign of the South Bank’s general affluence, which Robick certainly benefits from.

The commission even points this out to Robick, when he makes his case. Robick says that he has worked on his project for “many years” with “the naivete that it had benefited from your approval.” He restates his point from the prologue (which was created later), that the commission signed off on the plan, including Bridge Three. The commission responds that it has proved its admiration for Robick with “more than words.” It points out that Robick designed the High Commission building they’re currently in, and it implies that Robick’s been constructing for the commission for a decade — although it’s not clear that all of this time has been devoted to Robick’s large-scale reconstruction of the South Bank.

“But you’re an urbatect, not a politician,” the commission continues. “The two domains are close,” the commission acknowledges, admitting that architecture carries political ramifications. But it believes that Robick “cannot always measure the hidden implications of your plans.” It asserts that “the situation was different” when it approved those plans and ambiguously asserts that “the recent troubles” have forced the commission to harden its position. “Each new passage generates new weaknesses and necessitates new controls. It’s a risk we cannot take.”

It’s the first sign that the city may be subject to civil unrest, although it’s not clear how paranoid the commission is being. Obviously, states obsessed with control tend to be the most likely to hype their own security risks. It is, however, clear that Urbicande is not only a city divided but a semi-totalitarian state that wants to control the movement of its own population. In fact, it’s not going to far to say that the inhabitants of the North Bank seem deprived of basic civil rights, including movement, much like a people occupied by a wealthier, more prosperous power. Although Urbicande is a single city, it’s really two separate city-states, one of which dominates the other like a colonial power, and it’s telling that one needs a passport to cross from one bank to the other.

A dejected Robick narrates, “I asked Thomas to leave me alone, and I took a long walk before going back. I had to find another solution to bring balance to the project.” Clearly, he’s still obsessively focused on his project — so much so that he’s, quite logically, pondering architectural alternatives that will fix his design for the South Bank.

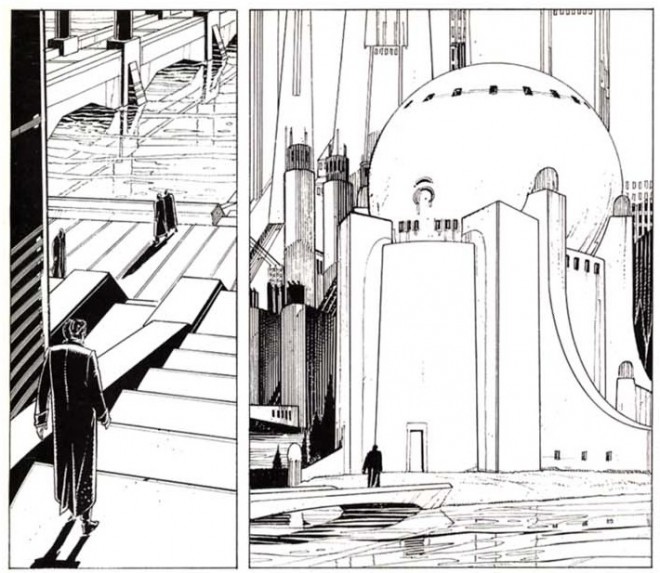

Robick’s walk occasions a few additional lovely shots of Urbicande, including Robick’s own office building, a beautiful round structure, defined by curves, with a sphere on its top — which seems to explain Robick’s huge office, with his map of this world drawn on its interior.

Notably, the building is actually rather different from most others in Urbicande, including those Robick has designed. First, it’s small compared to most others. Second, its beautiful curves contrast strongly with the mostly straight lines of the rest of Urbicande. It’s almost as if Robick, while intellectually preferring the kind of massive, linear structures that he’s designed for the city (and which reflect totalitarian architecture to some extent), prefers to actually live and work in a smaller, more intimate, and more inviting space. Without indicating so with plot, dialogue, or narration, Schuiten uses architecture to hint at character — particularly at a division within Robick himself. It’s a division we’ve already seen, between his professional obsession with his design and his unproductive fascination with the cube, and it’s one that will soon come to play a more obvious role in the plot.

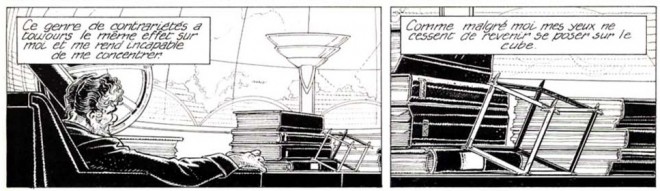

Back in his office, Robick narrates that he’s “too tired to continue work.” He says, “This type of confrontation always has the same effect on me and leaves me incapable of concentrating.” While easy to overlook, this is actually a key aspect of Robick’s character: he’s the sort of intellectual who avoids conflict, and he’s far more comfortable designing a city than he is in political or even personal relationships.

As the first chapter closes, a fatigued Robick sits at his desk and finds his eyes, “in spite of myself,” turning back to the cube. It’s as if he prefers the abstract intellectual puzzle of the cube to the political conflict of his design for the city.

The cube is resting at an angle, against a stack of books on Robick’s desk. That’s because Thomas left it that way, as he set it down on his way out of the office with Eugen.

Robick writes in his journal that he “had not noticed these points that prolonged, almost like buds, from each of the cube’s extremities.” He resigns himself to sleeping, knowing that he’ll get nothing more done, and closes his journal, thus ending the chapter. The final panel is of Robick’s closed journal, giving us a satisfactory sense of closure.

We can clearly see those “buds” on the cube, projecting out from both ends of the 12 lines that make up the cube. Each corner of the cube now has three little tips, extending beyond the cube itself, as if gesturing towards the cubes that might exist against the cube’s six faces. It’s like a mathematical or geometrical illustration, and it recalls the way we use the cube to illustrate an infinite three-dimensional space, as if the cube extends in all directions, when it fact its faces define limits to the space therein. It’s an appropriate image for a chapter about how we understand our own urban spaces.

But of course, there’s also a twist, and typical of the rather subtle series, it’s not one thrust upon the reader through dialogue or narration. Instead, it’s there in the artwork itself, spurring readers to flip back and reread more carefully this time.

Because when we saw the cube that morning, before Eugen and Thomas left the office, it didn’t have these “buds.”

It’s growing.

If there is a hint to this, in Robick’s narration, it’s that he calls the protrusions “buds,” that he reaches to an organic metaphor. It’s an odd choice, because there’s nothing obviously organic about the cube. Moreover, Robick’s an architect, and the city he’s designed has almost nothing by way of plant life. What he’s created is an ordered landscape of concrete. Yet the organic metaphor recalls the sundew pattern in The Walls of Samaris and the way Samaris is said to grow organically.

It also suggests Robick’s internal divisions, how he is not himself as controlled and ordered as the city he has built — and one suspects, as he’d like to believe about himself. Even his cartographic office walls suggests this control; maps represent the certainty of definitions, or the illusion thereof. Yet the shape of that wall and the building of which it’s part — curved, in a city mostly lacking curves — suggests something human and passionate, beneath Robick’s intellectual demeanor. And it’s worth noting that, while Robick doesn’t seem particularly apt at dealing with people and tells us he’s fatigued by confrontation, he’s obviously passionate about his design for the city, ranting and raving, an emotional response to which the cool Thomas provides a foil.

Those buds are literally the beginning of the cube’s growth. But they’re also the beginning of something stirring within Eugen.