François Schuiten Interview

It might have been the insomnia that sparked it all. Legendary Belgian cartoonist and illustrator François Schuiten recalls that he couldn’t sleep when he was a child, and he can still remember his mother’s voice reading him Jules Verne novels until he eventually submerged.

Or perhaps it was “Little Nemo in Slumberland.” Schuiten was twelve years old when Winsor McCay’s fantastical, early-century American comic strip was published in French — complete with lettering by Philippe Druillet, yet to become the famed science fiction writer and artist and one of France’s great creative forces. Young Schuiten devoured each brilliant page slowly, hoping the book would never end.

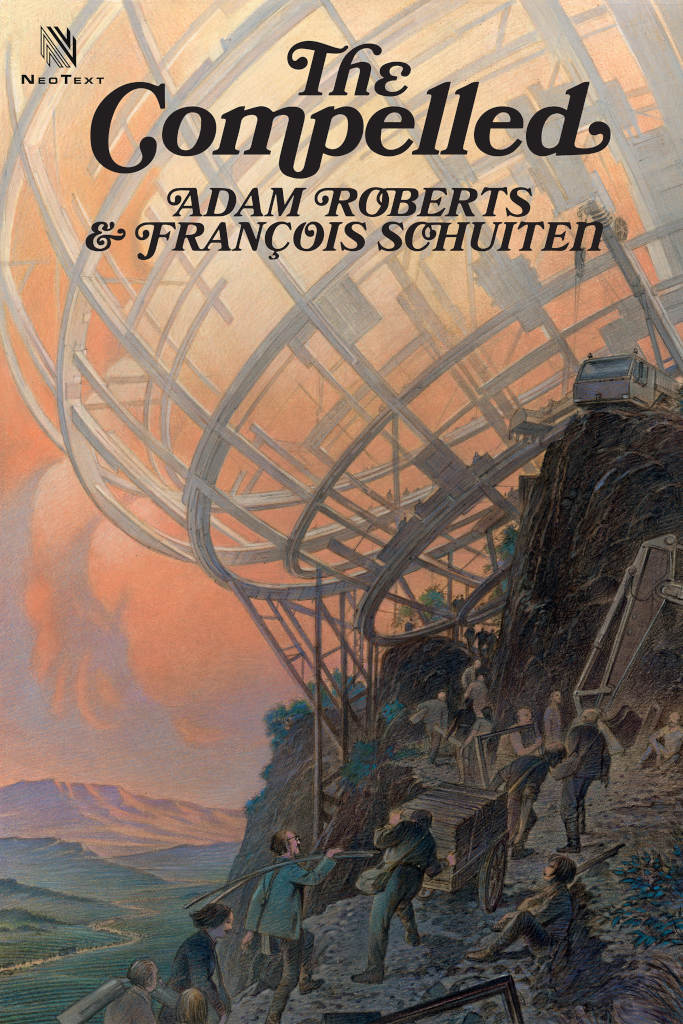

Certainly, Schuiten was influenced by early praise and encouragement from his father, an architect who noticed the artistry of a son who would grow up to create some of the most imaginative architectural wonders ever set to paper, including the multi-volume Les Cités obscures series, a collaboration with Benoît Peeters, and the new The Compelled, a collaboration with Adam Roberts for NeoText.

As Schuiten reveals in this wide-ranging interview, he was fueled by all this and more to become one of the leading lights of bande dessinee, the Franco-Belgian tradition of graphic narrative that developed alongside comics but, despite multiple borrowings and influences across borders and oceans, has its own distinct history.

Unlike the word “comics” — a word that carries a lasting whiff of old funny pages as well as an occasionally over-defensive denial of these origins — neither the designation bande dessinee nor its common abbreviation BD harkens to a past of gags and humor. As writer Cynthia Rose describes in a historic survey tied to the landmark 2015 French show L’âge d’or de la bande dessinée Belge, the story of bande dessinee “spirals out of Hergé’s inkwell.” It was 1929 when the Belgian cartoonist George “Hergé” Remi first published his wildly popular stories of an adventurous young reporter named TinTin, which eventually would be published in more than seventy languages. His success was noticed by other Belgian artists, and a movement was born.

“When Tintin first appeared, he was dropped into a Europe that worshiped Disney characters and made-in-America strips,” writes Rose. Following World War II’s occupations and liberations, Belgian talents blazed and new stories and characters strode onto center stage, pushing aside American comics. In this interview, Schuiten traces what happened next: just as these bold post-war innovations were starting to grow stale and repetitive, new publications such as Pilote and Métal Hurlant arrived to set Belgium once again as a center for bold experimentation in the narrative arts.

Central to these experiments were the art and stories of Schuiten. In this interview, Schuiten cites Jean Giraud, who as Moebius created the popular Western anti-hero Blueberry, influencing filmmaker Federico Fellini as well as helping to create visuals for movies such as Alien. “Moebius said a story is like a house, everybody wants us to walk into the house through the door,” Schuiten says. “I want to walk in through the window.” Here, Schuiten speaks of his half-century of climbing through multiple windows into multiple houses, across multiple cities — real and imagined.

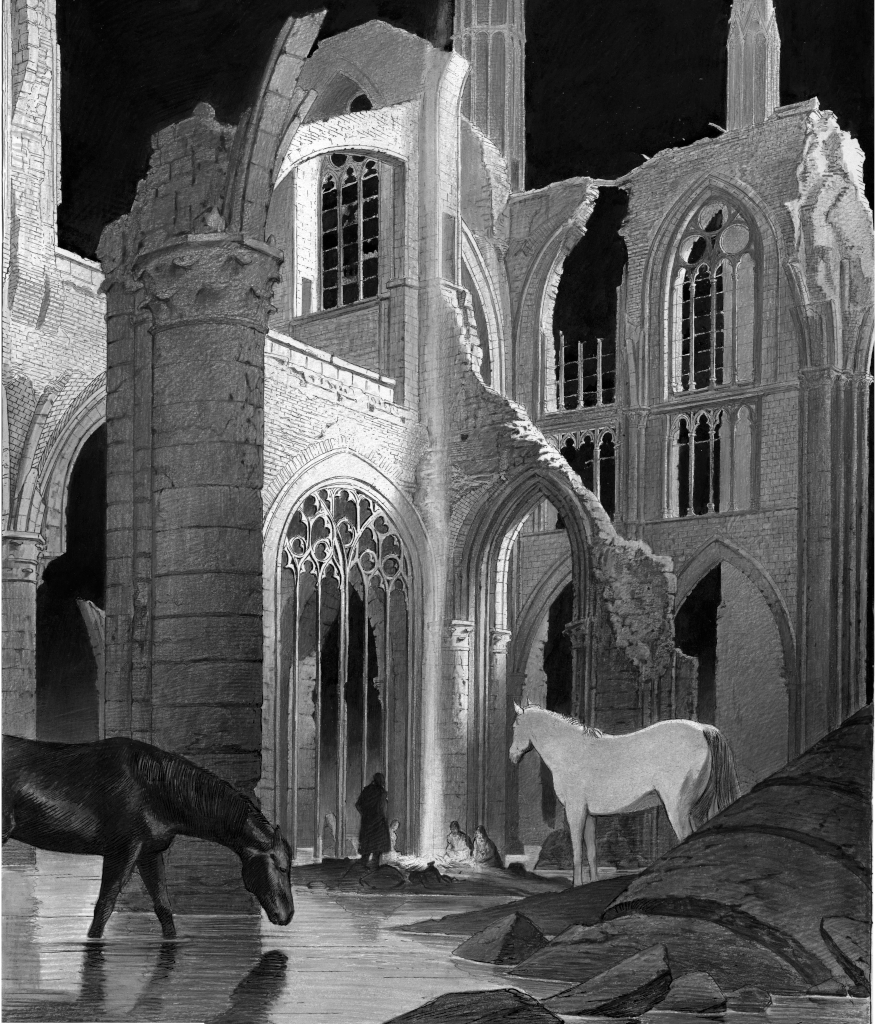

The interview was conducted via Skype with translation by Deborah Kaufmann. As Schuiten talked, he sat before a giant painting by Belgian artists Gustave Wapers and Eugène Verboekhoven, showing Victor Hugo's Notre Dame de Paris with Quasimodo and Esmeralda in its center. The painting belonged to Schuiten’s grandmother; he still remembers being terrified of Quasimodo. The interview was interrupted on just one occasion by Schuiten’s large dog named Jim — for Jungle Jim, the lead character in an American adventure comic strip by Alex Raymond.

TISSERAND: How are you doing in these strange times? How are these times affecting your work and your day-to-day life?

SCHUITEN: If you’re able to handle the crisis, it actually nurtures reflection, concentration and creativity. It fuels it. Right now, my work is taking me to the planet Mars. And sometimes I feel like Earth is like planet Mars. It has the same dissociative feeling, alien feeling. It’s another world.

TISSERAND: Your work already deals with the vastness of history, so this feels like just one more page in that work?

SCHUITEN: Perhaps. Books and the bandes dessinées that I love are those that are in conversation with their time.

They don’t really know how these things happen. John Ford’s Westerns, but also science fiction movies like Metropolis or Blade Runner, are extremely multi-layered and touch very deeply on the nightmares and the dreams of their times.

His art is ahead of him

TISSERAND: What examples do you see in bande dessinée?

SCHUITEN: Hergé is a terrific example of someone who had a profound understanding of his time, for better and worse. The worse is in the beginning of his work. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Tintin in the Congo are two examples of where there is no filter. Gradually, from these initial books, Hergé starts deciphering, analyzing, understanding his world. I think it’s an extraordinary story, because he evolves as a human being through his books and through his work. You can actually see that happening. His art is ahead of him, it matures ahead of him.

TISSERAND: By no filters, you mean the works have racial stereotypes, raw stories of colonialism?

SCHUITEN: Yes, of course. Clichés of America, also. On the Congo, on communism. He’s a really young citizen of his time. He started when he was very young and he knew nothing. And Tintin teaches him about the world and Hergé will learn through these stories.

TISSERAND: When we say the phrase “bande dessinée,” what are we talking about? Do you consider it a school or a movement, or is it just a big category? It has different connotations than words like “comics” or “funnies,” which still have at least an echo of humor in them.

SCHUITEN: Forty years ago when I started out, I would have said something totally different from what I’m about to say now. If you just draw a succession of strips and text and images, with any extravagant layouts, it would work as bande dessinée without any particular rules. That would not have qualified as bande dessinée forty, fifty years ago.

There are so many forms of bande dessinée today it is hard to describe. I don’t feel that it is my job to determine if one thing is bande dessinée and the other thing isn’t. It’s something I encountered when I was young and I hated that.

It is true that comics and funnies have an element of levity, when bande dessinée does not have the kind of designation in Europe. When the term graphic novel was introduced, the gravitas was necessary in the United States, but it probably wasn’t as necessary in Europe. There were bande dessinée for adults in Europe, long before graphic novels, with serious content.

Breaking out of the panels

TISSERAND: So when you were starting out, there were questions and controversies about what is true bande dessinée, perhaps similar to debates about what is truly jazz music?

SCHUITEN: Any attempt to compartmentalize or to pigeonhole one or the other is hugely problematic for me. My entire ambition is to get out of the box, break out of the panels.

TISSERAND: So you were told your work was not proper bande dessinée in your early career?

SCHUITEN: Yes. I started hearing that criticism when the magazine I belonged to, Pilot, started hiring people like Philippe Druillet or Moebius, and people were shaking their heads and saying this is not bande dessinée. They were anticipating a movement that would take bande dessinée away from being a children’s medium to an adult readership.

A similar revolution happened in the United States with the “The Yellow Kid” by Richard Outcault, and with “Little Nemo” by Winsor McCay, who is the master of all masters. When newspapers started publishing this expression, it’s the key, it’s the turning point. These artists, they should have museums, statues, they should have monuments in their name. They are creators to whom I and all my contemporaries always refer to, they are always in our works.

TISSERAND: Why is Winsor McCay your master of masters? When did you first start reading him?

SCHUITEN: I was twelve. There was a big French edition of “Little Nemo” published by Pierre Horay and the lettering was done by a very young Philippe Druillet. He did the whole French text. I can see the book still. For me, it’s not a coincidence that you have the forefather of comics and Druillet who will come and revolutionize the genre entirely. You have the ancient and the modern. I think that is why it was so powerful to me.

McCay invented a language. He’s an extremely modern man by the way that he witnesses his world and his time, the techniques he uses to bring his work to print, the way he fills the whole format of the newspaper, the space. He is almost one of the first persons to invent comics. He’s one of the first people to invent animated cartoons. He creates live shows that blend in animation and live drawings. And he’s a newspaper artist, who will illustrate the news. For me, he’s the ultimate role model because he’s the modern man who explores every medium, who tries every form.

TISSERAND: In a “Little Nemo” comic, objects might become animated, a bed might become a horse and then gallop over the city. Sizes compact and expand. Did those elements in “Nemo” capture your imagination?

SCHUITEN: Yes. I was so fascinated with the book I would make myself stop after a couple pages to make sure I didn’t get to the end too fast. It was so generous, so funny, so full of imagination, there was everything in that book. Everything. He created dream worlds, but they were also extremely credible, and extremely well-constructed and structured.

TISSERAND: What is the first time you remember drawing?

SCHUITEN: I have one very vivid recollection. My father was a painter and an architect and an artist. I remember being in the living room, and there was a big cedar tree in the garden. I had observed that cedar very, very carefully. His father was astonished by my drawing because he realized that I hadn’t imagined the tree; I had observed the tree. Because of this cedar, my father said, “You will be an artist, you will draw.”

TISSERAND: He said an artist, not an architect?

SCHUITEN: My father had a hierarchy of arts and for him, painting was at the very top. Unfortunately, bande dessinée was at the very bottom.

TISSERAND: Did this lead to any difficult father-son discussions?

SCHUITEN: He always hoped his son would become a painter. But I always admired and respected my father very much, and there was no conflict.

Mysteries and myths

TISSERAND: I have to ask when you encountered “Krazy Kat” and if that also made an impression on you?

SCHUITEN: Much, much later. It wasn’t an early influence. I own an original page of George Herriman’s work and I find it extraordinary. The font, the lettering, the typographic work. How he articulates the text with the image. He invents the language. I don’t understand artists who do not draw their text. The text is art and art is text, and you need to know how to do both. This is really at the heart of comics and bande dessinée art.

I’ve always been fascinated by the history of comics and bande dessinée. To me, it’s fundamental, and I don’t understand how young artists emerging today can disregard that history entirely.

TISSERAND: When you look at George Herriman’s desert and Winsor McCay’s city, you see how each viewed setting as critical to their comics.

SCHUITEN: What I’m fascinated about with Herriman is the stage that he builds. There’s also a language that Herriman invents. The lettering, how the story is structured, the different points of views, the characters, all this constitutes the language of comics.

TISSERAND: Staying on early influences, you illustrated Jules Verne’s Paris in the 20th Century when it was finally published after his death. And I know you have long been a fan of his books. When did you first read Jules Verne?

SCHUITEN: I suffered from insomnia and my mother would read me Jules Verne. It was dream-inducing. It helped me fall asleep.

TISSERAND: Did Jules Verne’s language and your dreams merge on those nights?

SCHUITEN: I would revisit the stories and look at the original illustrations, and in my mind, my mother’s voice and those illustrations would blend.

TISSERAND: That’s absolutely lovely.

SCHUITEN: And it’s true! I didn’t make it up.

TISSERAND: Why should people still read Jules Verne? How would you sell someone on the importance of still reading him? Where is the meaning for you?

SCHUITEN: I’m not entirely sure how to sell Jules Verne. I’m completely sold. It’s a name that people know but people don’t read anymore. And it saddens me.

I am working specifically for the city of Amiens in France, which is the city where Jules Verne wrote most of his novels. I’m working on an installation on the square in front of the train station. It’s a real return to childhood for me. It was a stone square — very, very cold. The residents of the city hated it. So a few months ago we installed a bamboo forest, eight meters high. Toward the end of the year, there will be a water wall on which we will project images from Jules Verne’s works. The third chapter in this adventure will be a gigantic octopus – half octopus, half nautilus. And it will be immersed in water. And it will be called Octopus Garden, like the Beatles song.

That’s how you make people read Jules Verne.

TISSERAND: If I pick up a Jules Verne book to read at the end of this interview, which one should I pick up?

SCHUITEN: The Mysterious Island or Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Five Weeks in a Balloon. I love From The Earth to the Moon.

TISSERAND: In this year, it feels like we’re contracting. Jules Verne’s work is ever-expanding, which I feel in your work, also.

SCHUITEN: What fascinates with Jules Verne is his absolutely scrupulous scientific approach. It’s almost too didactic. But this scrupulous approach to cutting-edge reality and then this expansion of imagination. And that’s the extraordinary blend. His ability to understand the mysteries and myths of his time, and explain them to his contemporaries. He had this ability to make them dream about — to be in awe of — these mysteries.

Everything seemed possible

TISSERAND: You were sixteen when you first published in Pilote magazine. How did that come about and what was that first published work? I was looking for that but couldn’t locate it.

SCHUITEN: I’m not sure you should find it. (Laughs.) The first time is always the most beautiful. I was a shy kid, I wasn’t an excellent student, so it was important to realize myself in some other way. And to be published by the most extraordinary magazine of that time, with “Blueberry,” “Lone Sloane”, Gotlib, all these creations. The people I revered. It gave me wings.

TISSERAND: What was that first work?

SCHUITEN: It took me about six months to draw. There were five pages. Every panel, I drew possibly ten times. I didn’t understand that I was being paid for my drawing, I would have paid to be in the magazine. The editor-in-chief told me I was the youngest artist they’d ever included.

TISSERAND: Was it an adventure tale?

SCHUITEN: It was a vampire story. (Laughs.) I didn’t continue in that vein.

TISSERAND: When did Métal hurlant come onto the scene and how was it important in the development of bande dessinée?

SCHUITEN: When Métal hurlant arrived it was an absolute shock. An incredible shock to everybody. We were under the impression that doors, windows opened, everything opened. All of a sudden, everything seemed possible.

The magazine was at the confluence of rock music, of cinema, of art, fantasy. It was the epicenter of all these seismic layers.

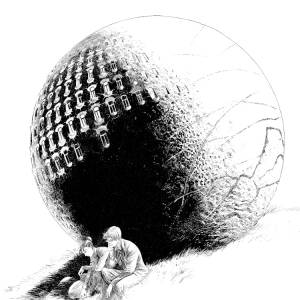

I was published in the thirteenth issue of Métal hurlant. The story I did is called “Carapaces,” which translates to a shell on a tortoise. It was in 1977 and I still feel a very strong connection to that story. I’m not going to say don’t find that one.

TISSERAND: What was it about it that was so revolutionary, that blew open all the doors?

SCHUITEN: Bande dessinée at the time was a generation that seemed like it was dying. The two main publications, Spirou and Tintin, the readership is children. They had been transformative after World War II. For a decade perhaps Belgian bande dessinée was the most extraordinary in the world. But it was weary and it was repeating old recipes.

Métal hurlant broke this model because it was an independent creators’ model. Only the creators were involved and it was self-published.

TISSERAND: Was the content controversial? Did it test the boundaries of censorship?

SCHUITEN: Not so much at Métal hurlant. Censorship affected Fluide Glacial because that’s where Gotlib was pushing the boundaries of nudity and propriety. Métal hurlant pushed boundaries in terms of storytelling. What is a story? How do you tell a story? It was different in that sense.

Moebius said a story is like a house, everybody wants us to walk into the house through the door. I want to walk in through the window.

Collaborations

TISSERAND: Your career in storytelling has included so many collaborations. What do these collaborations look like as a process?

SCHUITEN: I love collaboration. With Benoît Peeters, we imagine the story together. It isn’t the same each time. We could start around a conversation about the story, or it could start from a drawing. I don’t like to compartmentalize the work. What matters is there’s chemistry, something happens.

There are no rules. I like to change methods and adapt to whoever I’m working with. I think that I myself am also the writer, maybe even writing the dialogues. And Benoît perhaps thinks that he’s also an artist, even if he doesn’t draw. It’s a common thread of thought. I don’t even remember whose ideas came from who,

I don’t really care about that. There’s no ownership. I don’t care.

TISSERAND: In your new book with Adam Roberts, The Compelled, what did that collaboration look like?

SCHUITEN: The Compelled was an idea of John Schoenfelder’s, and the whole idea of putting me together with Adam around the concept, that came from John. And the concept was John’s, also. Adam wrote the story and I added my own ideas in terms of world building, and there are a lot of conversations, and in the end nobody remembers the process.

There was a lot of trial and error. The best projects are the ones in which it’s not entirely clear what you’re doing. The project doesn’t really belong to any one of us, it was just in our midst. I like to be used to make prototypes, not industrial work. I don’t know how to capitalize on characters, like many of my colleagues have been successful in doing. It’s not my thing. It’s not something I want, but it’s also not something I think I’m capable of.

There’s always the blank page at the beginning of every project.

TISSERAND: You like the blank page?

SCHUITEN: Yes. It gives you a kick in the ass, that’s what the blank page does.

TISSERAND: When I write, the blank page terrifies me and I just fill it with shit just to get something on it, and then I go to work.

SCHUITEN: But it’s so exciting.

Saving the world

TISSERAND: When I read The Compelled and look at your work on it, it reminded me of something you once said about your work on “Blake and Mortimer,” that the question is what does it mean in one’s own time to save the world. It seems to resonate now, in our moment in history.

SCHUITEN: It’s interesting to see how the focus of the preoccupation changes with time. We’re not as scared about the A-bomb, or nuclear catastrophe. Maybe we should be, but we’re not as much, we’ve moved on. But we’re still obsessed with the idea of saving the world.

TISSERAND: We don’t talk about it, but those weapons and the dangers are still right there.

SCHUITEN: Exactly. Every period in history has its blind spots, and its hyper-focal spots. There are times in history where tiny little streams will become rivers and there are times in history when rivers just flow into the ocean. We’re consumed by fantasies that grow, and fantasies that shrink and shrivel and die, according to our time in history.

TISSERAND: What is our fantasy now, compared to Blake and Mortimer’s time, or Jules Verne’s time.

SCHUITEN: Blake and Mortimer’s world is a bipolar world with bad guys and good guys. It’s the world of post-World War II. It’s very clear, it’s very clearly defined. Today, in a world extremely complex, the danger would be to oversimplify it.

The complexity is unavoidable. It is something that artists have to take into account, to address the complexity of this world. Not use yesterday’s cliches. It’s an absolute quest, to search for the signifiers of today, that wouldn’t be caricature.

TISSERAND: Are you able to discuss this complexity more in your visual art than in a conversation like this?

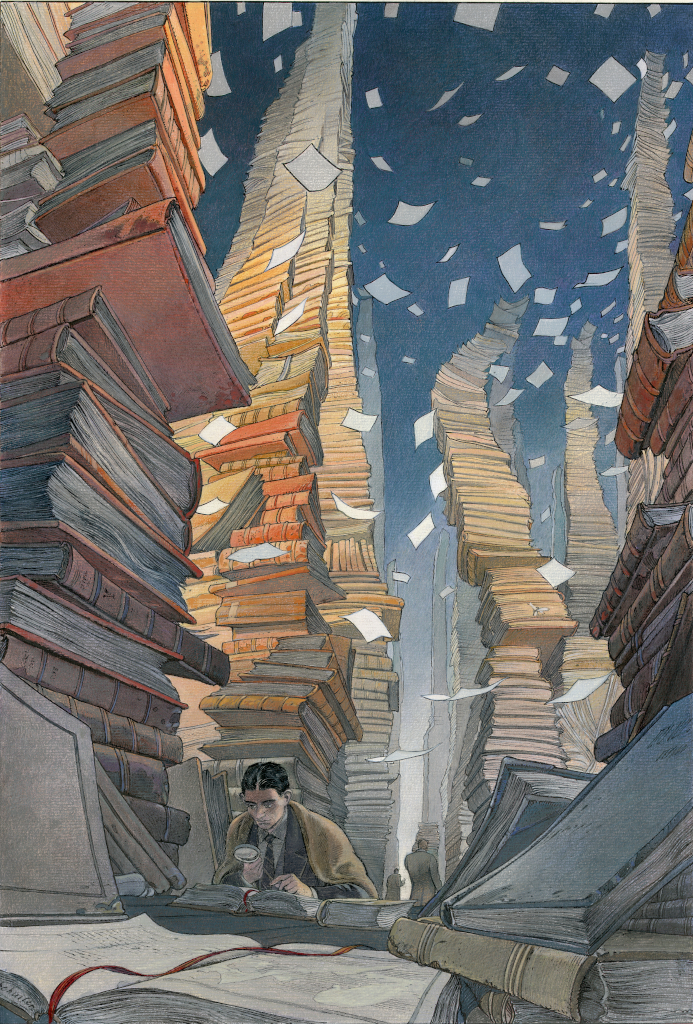

SCHUITEN: Yes. For me, my art helps me to understand the world. Until I’ve drawn it, I don’t really know it.

TISSERAND: That’s exactly what you said about Hergé, the art leads the man.

SCHUITEN: With Hergé, what was wonderful was his intuition. There’s a progression in each book, and we can be witness to that progression. I’m very moved by the fact that the artist grows through his works.

TISSERAND: And you experience this yourself?

SCHUITEN: I try.

A blind machine

TISSERAND: I see in a number of bande dessinée works, and in your work especially, you are wrestling with man, with machines and our cities.

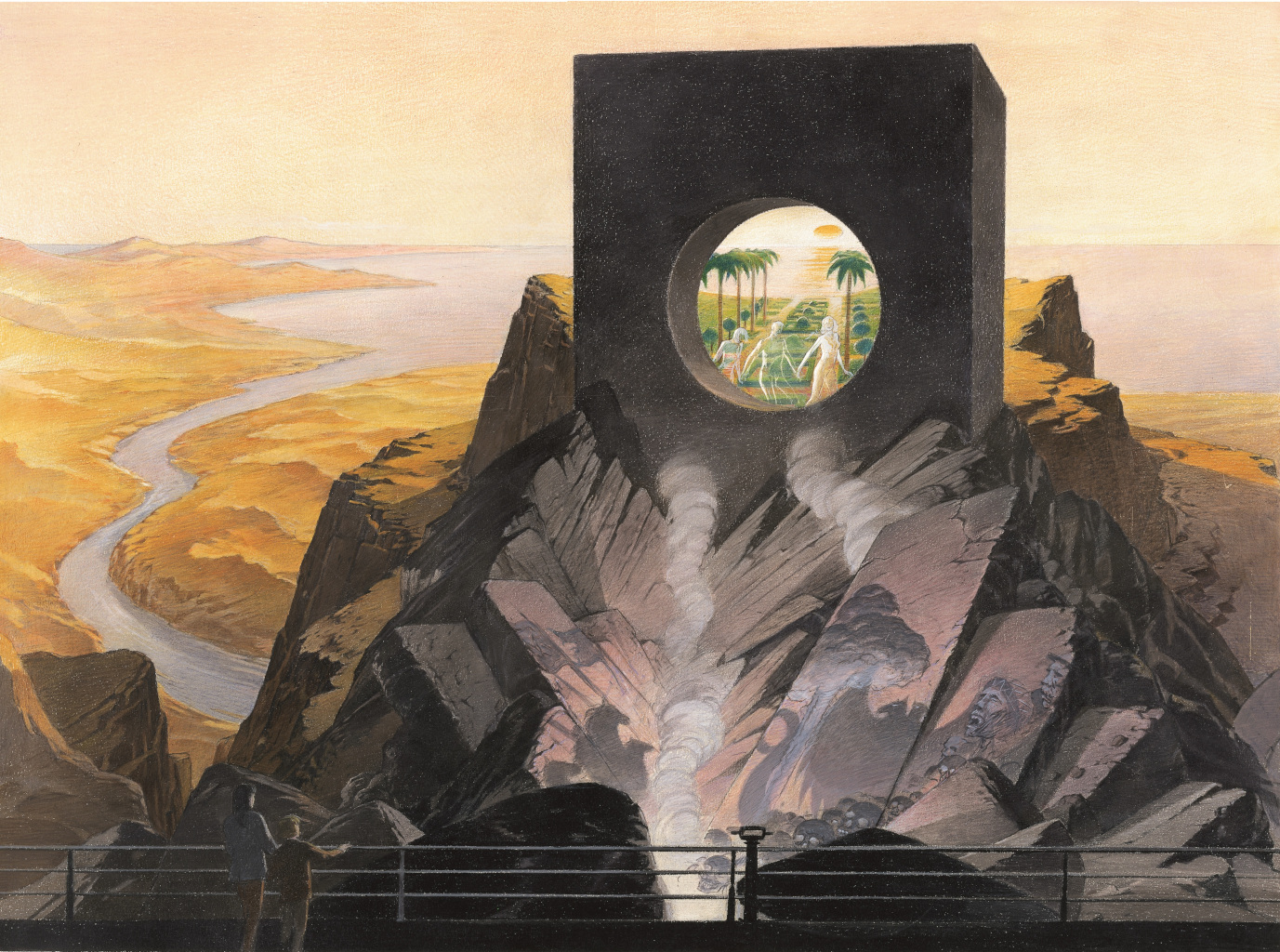

SCHUITEN: The art is an image of the system. The system is not really drawable, it’s invisible, it’s not something you should be able to reduce to paper. We have to translate it and give it a shape.

TISSERAND: By system you mean social system, political system, economic system?

SCHUITEN: That’s the machine. And it’s a blind machine. What I try to do is find shapes that echo these questions.

TISSERAND: One thing I noticed that as I spend time with your art, it changes the way I go about my day. I think I usually live my life sort of in mid-range, but after immersing myself in your work, the scope widens. I pay more attention to the buildings, the streets, the greater world. Many comics are about two people talking. You work on a much wider scale.

SCHUITEN: My Holy Grail is creating an image that will set itself in your fantasy world. It integrates itself there. There are some images that become embedded in your retina. That’s my ambition. We live under image overload right now. There are so many images all around us. There is a lot of flattering technology. The question is how an image resists against all this. This is a question that really haunts me because images can wear themselves out. They become as smooth as pebbles in a river. That’s not what you want.

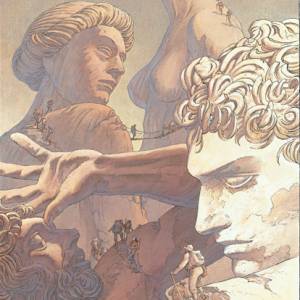

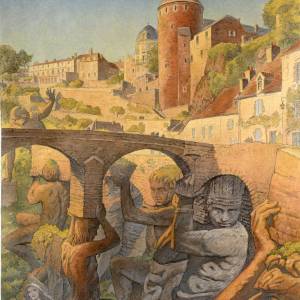

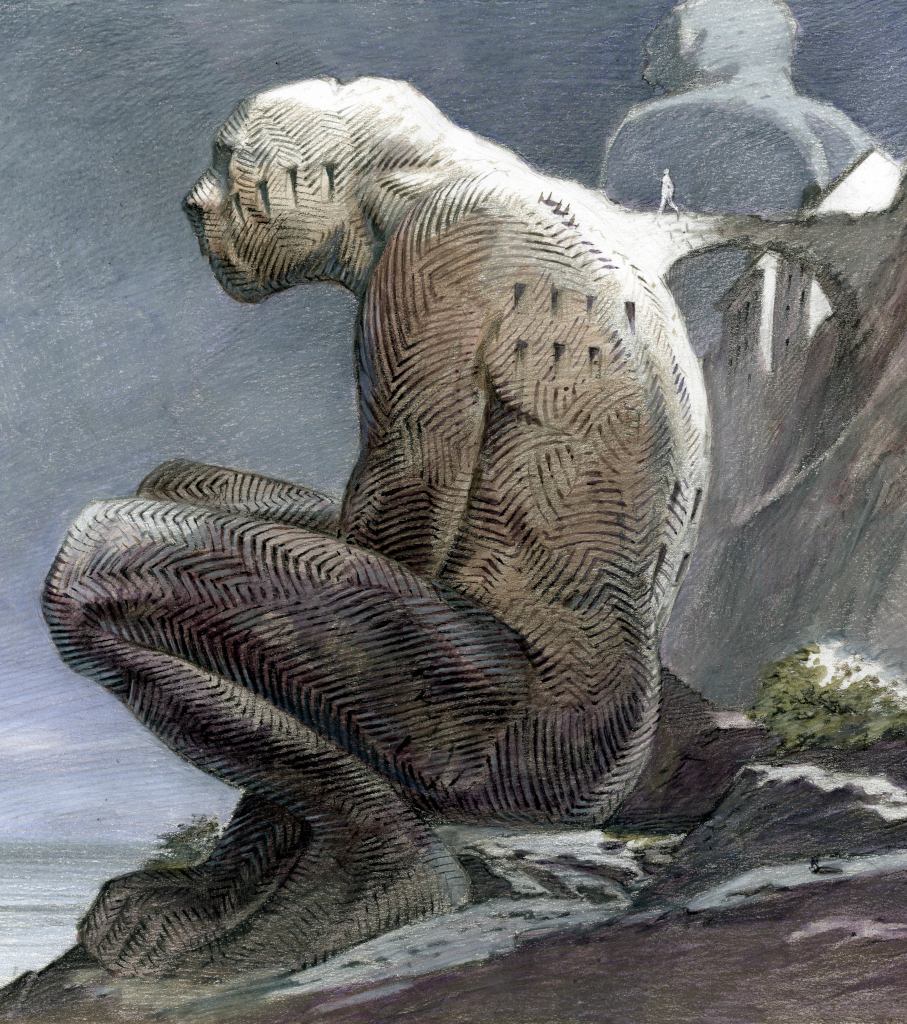

TISSERAND: One example of these images that embed themselves is your living statues.

SCHUITEN: The history of how these images came about is actually very interesting. I was approached to create the background of a video game. It was a Belgian project and it fell through. I showed these illustrations to a writer I love, Jacques Abeille, and it led to the book, Les Mers Perdues. Previously I had illustrated his trilogy, The Statuary Gardens, an incredible story, very fantastic, very surrealistic. He writes like a surrealist, more so than a science fiction or fantasy author. He doesn’t have the characteristics of a French novelist.

TISSERAND: Is surrealism important if you are trying to give shape to an invisible system?

SCHUITEN: Yes. The surrealist movement was extremely important in Belgium. There are novelists, poets, photographers, not only the artists like Magritte or Delvaux, or others whom you may know. It was a very big movement. It was a lifestyle. It’s something that’s very deep and is deeply rooted in Belgian imagination and fantasy.

TISSERAND: The living statue series spoke to me of the current social and political struggles over statues, and how we use statues to see our own history. The life and death of statues is a real concern these days.

SCHUITEN: Not just in the United States, but in Europe also. What I like about the statues is I didn’t make them on purpose. I wasn’t controlling the narrative. They just came about. The artist came to life.

The layers of cities

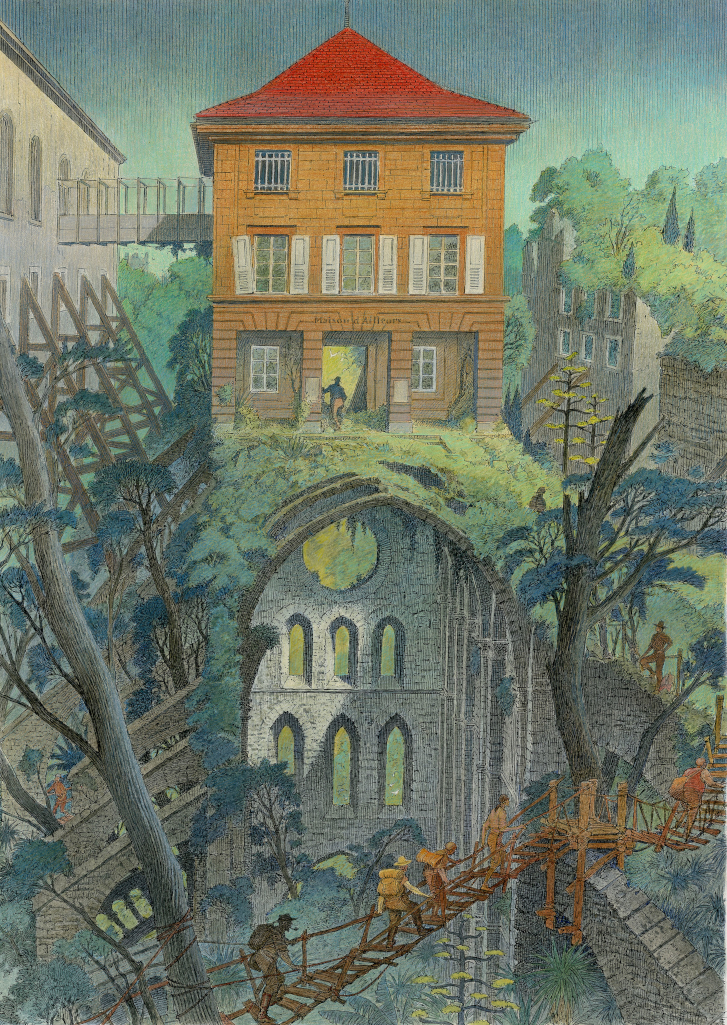

TISSERAND: You made it part of your personal mission to help save the Maison Autrique, the Art Nouveau house built by the famed Belgian architect Victor Horta. Why was that type of project important to you?

SCHUITEN: And also the Palace of Justice, which is mentioned in “Blake and Mortimer”. Sometimes it’s interesting to fictionalize reality to speak about reality and do something about reality. When the book Brusel was published, it raised some controversy. It was critical about what was going on in Brussels but it was really a love letter to the town.

I’ve always been pulled in two directions — working through absolute fiction and the most fantastical fiction on the one hand, but also working to impact reality even in tiny little ways. And with the Maison Autrique, it was an obvious need to embody the ideals we were so concerned with.

TISSERAND: What ideals?

SCHUITEN: The Maison Autrique allows people to enter the intimacy of a home. Not a palace, not a masterpiece, but a home. A very traditional classical house. A modest house even. The person who owned it wasn’t a person of many means. And the neighborhood was at the time rather rough.

There’s an imagination in every home, in every house.

TISSERAND: What do cities lose when they lose these sites of history and beauty?

SCHUITEN: It’s a piece of ourselves that we lose. What’s beautiful in a city are all the strata, all the layers — like a mille-feuilles pastry. The beauty in a city is its ability to accept all these layers.

TISSERAND: What is your personal favorite city?

SCHUITEN: I spend my time between Paris and Brussels. There are things I absolutely love about both cities and things I hate.

TISSERAND: Besides those two cities?

SCHUITEN: I’m not crazy about iconic cities – Venice, Bruges … they’re too pretty. I like the mystery of a city that didn’t entirely control its growth. That grows out of itself and escapes any type of control.

What I like about Brussels is the Palace of Justice, which is gigantic, out of control, but also abandoned, it’s not used anymore. And it tells so many stories. A thousand and one stories emerge from that place if you try to make sense out of it.

What I like about Brussels is it’s a bit of a patchwork of a city, it has Spanish influences, French influences, British influences, Dutch influences.

TISSERAND: I love that idea of an uncontrolled city.

SCHUITEN: Because this is what allows you to be in a relationship with the world. It’s not a reassuring city. It’s a city that translates the contradictions of the world.

TISSERAND: Are those the types of cities that you find yourself creating in your work?

SCHUITEN: I love cities that make me feel passionate, anxious, in love, and furious.

The in-between

TISSERAND: You’ve worked in movies as well as comics. What is the difference between watching a movie and reading a comic? Does that difference affect your approach as a creator?

SCHUITEN: It’s huge. In my opinion, bande dessinées and movies are completely different, they have nothing in common. The reader of a bande dessinée, like any book, is in his own time. You travel in the panel in your own rhythm. Whereas in cinema, the time is the director’s. To think that you can just adapt a comic into a movie … Americans seem to know how to do this, with Europeans it’s more of a disaster.

A lot of people seem to think that bande dessinée or a comic book is just a storyboard and it’s very naive. There are bridges between them, but the language of each is completely independent and different. When you’re still building the world, when you’re still imagining the characters and the storylines, that’s when maybe the two art forms are the closest, at a preliminary stage.

TISSERAND: Do you believe like your father there is a hierarchy of arts, or do you see it all as one big creative expression?

SCHUITEN: I don’t think there’s a hierarchy and I find myself in the intermediary arts. I’m very happy in the in-between. That’s my comfort zone. I love bande dessinée which is a dialogue between text and images. I worked on one of the first CGI series, The Quarks.

I don’t think I’m quite up to pure arts.

TISSERAND: What movies do you think capture the comics experience the best?

SCHUITEN: Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight series reinvented comic book adaptation. Even Tim Burton’s Batman. It was very interesting to me, the way both adapted the comic book into film. There are great examples but there are also examples of disasters.

TISSERAND: Such as?

SCHUITEN: Gaston. It was absurd to even contemplate adapting for cinema a work that is so absolutely graphic. It’s pure visual.

TISSERAND: What would you like to do professionally that you haven’t had the chance to do yet?

SCHUITEN: One of the reasons I agreed to take on The Compelled is to be part of a film project in a way I haven’t been part of yet. I’m working on a project in Canada where I will be drawing on stage, with a musician and dancer. That’s a little bit like what Windsor McCay used to do.

TISSERAND: It will be your “Gertie the Dinosaur.”

SCHUITEN: Exactly. I want people to reconnect with the feeling of absolute wonder that audiences must have felt at the time

TISSERAND: I think we can all use a little wonder right now. Your worlds are very surreal and dreamlike, but do you find over the years that any of your creations have had a predictive element?

SCHUITEN: I’m not really aware of that. It’s not my job.

TISSERAND: You never stumbled into it?

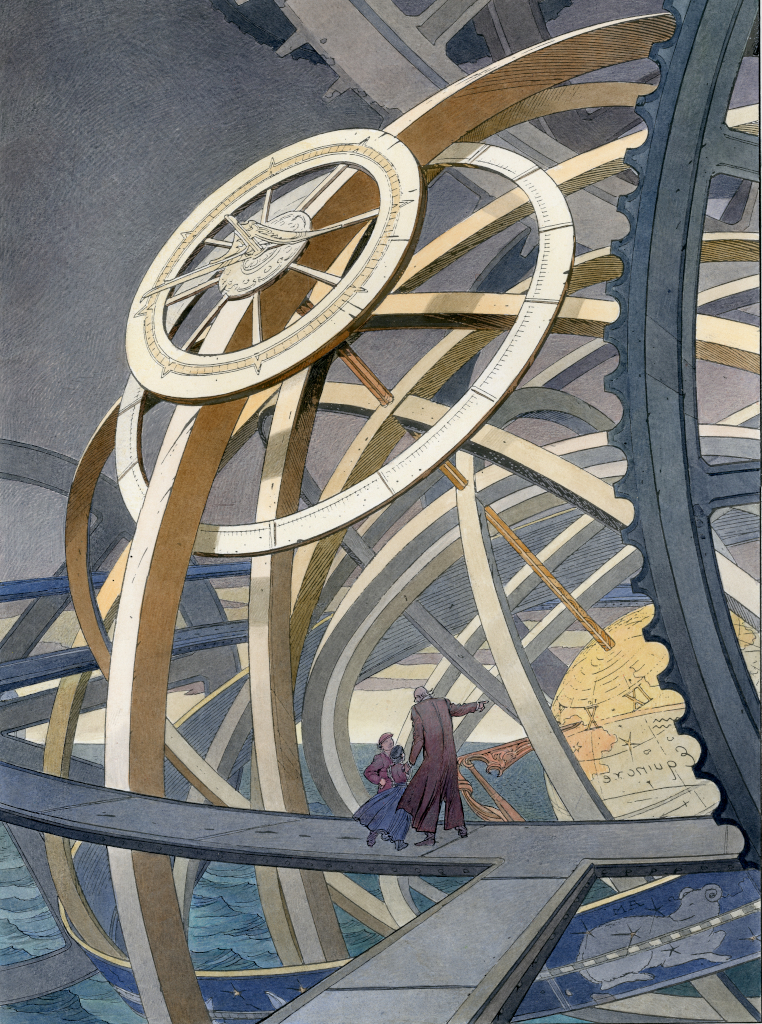

SCHUITEN: I just reread something of mine, an early work, called “La Fièvre d’Urbicande”. because they are doing a new color version. It was during the beginning of confinement. It was almost scary.

TISSERAND: Why?

SCHUITEN: It’s about a network that seems to grow and grow and grow, and contaminate the world. In “Carapaces,” people have very weird relationships because they are mostly covered with a shell. Some people are also telling me that story resonates with what we’re living with right now, because we’re all living in a shell. The shell is manifested on our faces and there’s just a little bit of ourselves that is coming out.

TISSERAND: Where did you get that initial idea?

SCHUITEN: It’s hard for me to say where the ideas come from. They haunt you and then they just have to get out. We have sensors and we sense the world.

TISSERAND: Something like what Ezra Pound once called invisible antennae?

SCHUITEN: I feel that everybody had that kind of interaction with the world. Art is the tool to give shape to that.

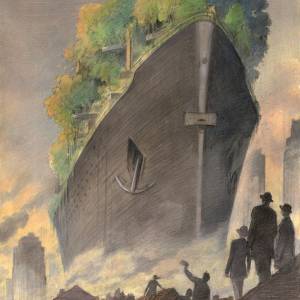

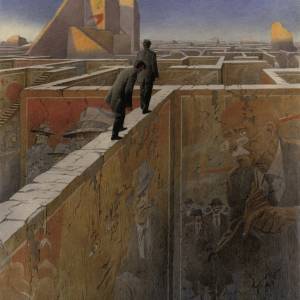

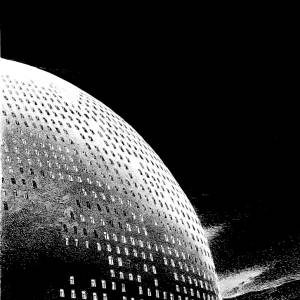

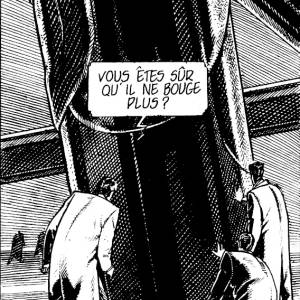

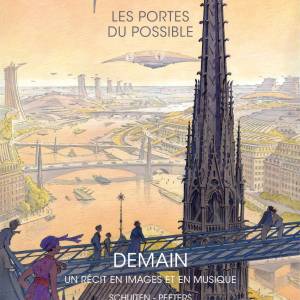

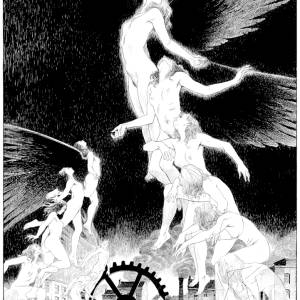

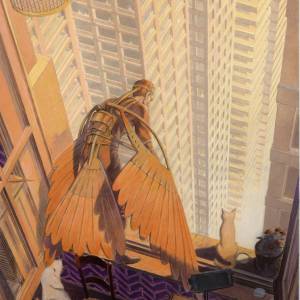

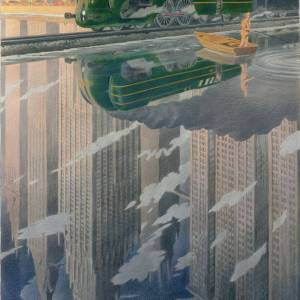

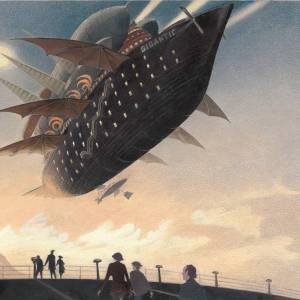

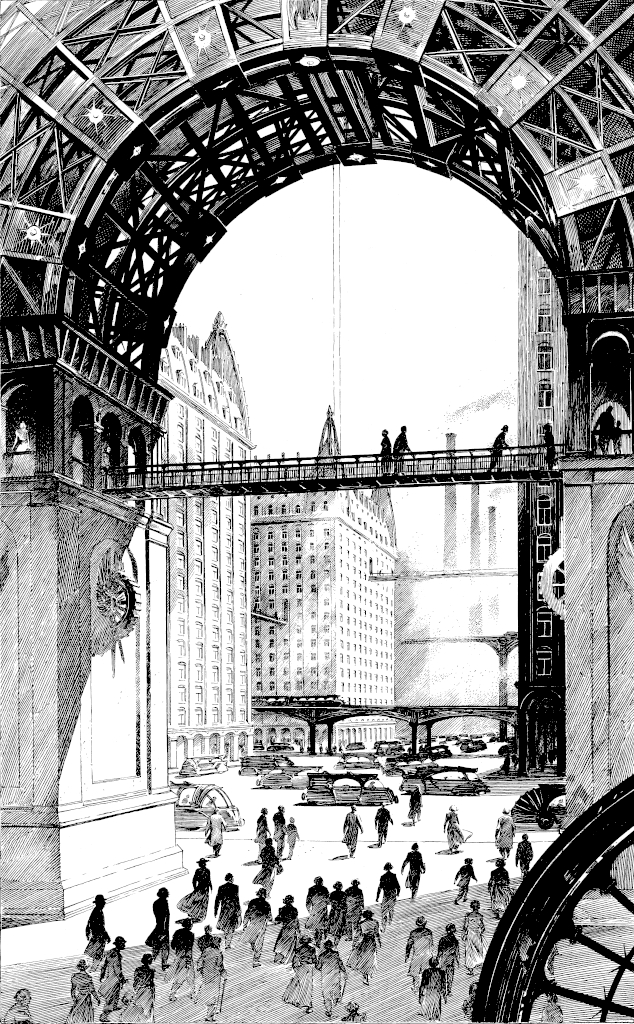

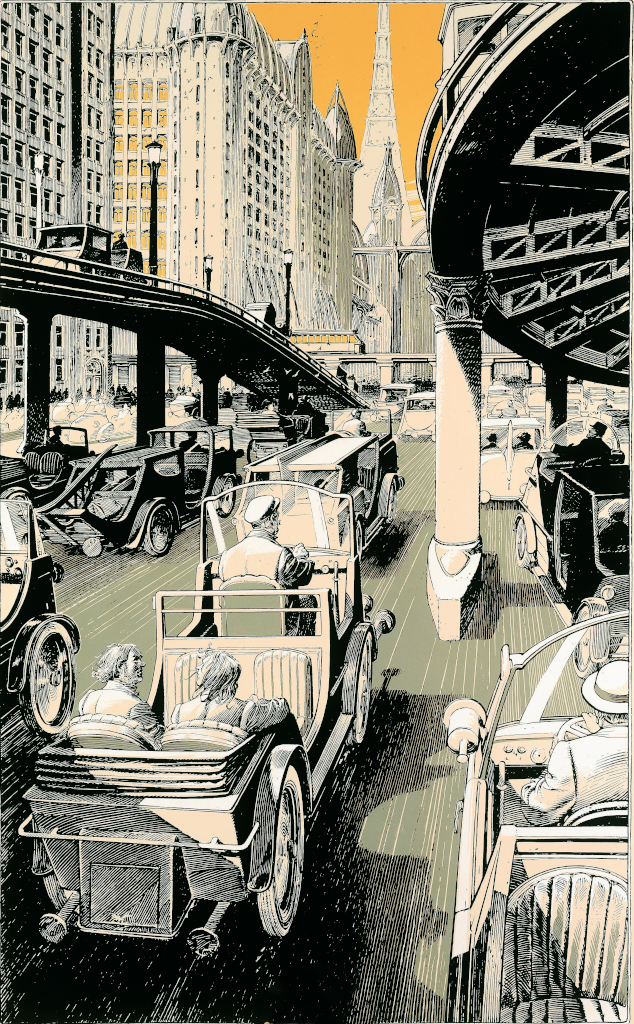

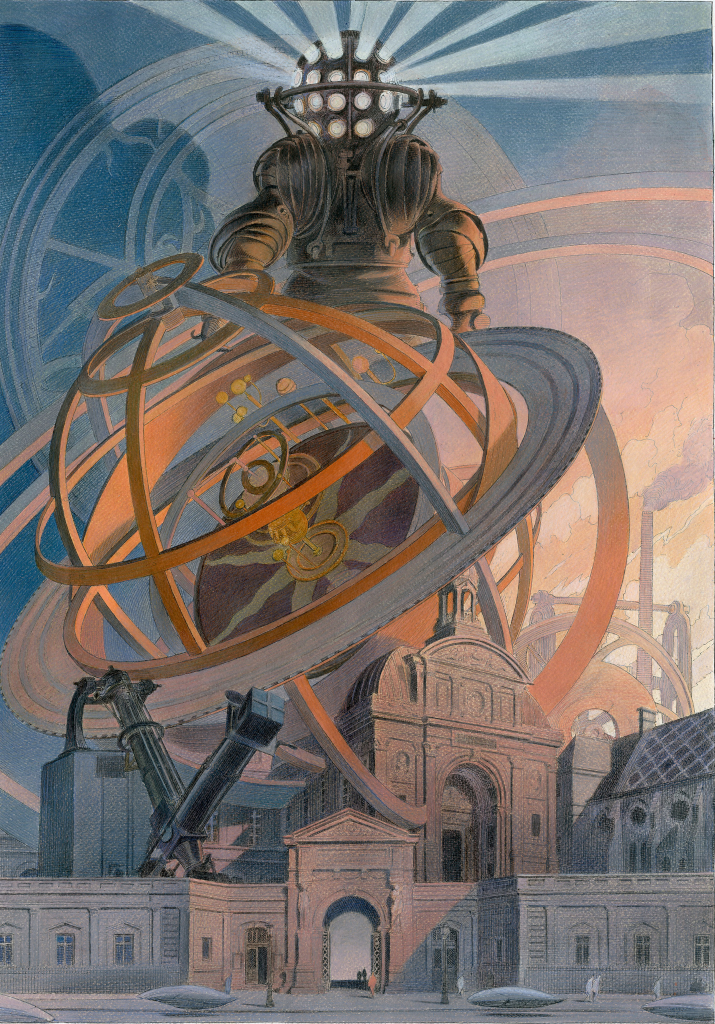

The above artwork is reproduced from L'Horloger du Rêve, by François Schuiten, Benoît Peeters and Thierry Bellefroid, © Editions Casterman. All rights to these illustrations are reserved and all these illustrations are protected by copyright and cannot be used without the authorization of Editions Casterman.

MICHAEL TISSERAND is a New Orleans-based author whose most recent book is Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White — the Eisner Award-winning biography of cartoonist George Herriman, the creator of Krazy Kat .

Original article by Michael Tisserand, published at January 2021.

Read the original publication at

NeoText